The long ball enthralls us all, regardless of the sport. In baseball, Barry Bonds is the current king, but the McGwire/Sosa race remains fresh in our minds. In football, it’s the hail mary. And in golf, it’s the 350-yard drive. The drive that makes 550-yard par fives reachable with 6-irons and renders long par fours defenseless against an onslaught of high-arcing short irons and wedges.

The long ball enthralls us all, regardless of the sport. In baseball, Barry Bonds is the current king, but the McGwire/Sosa race remains fresh in our minds. In football, it’s the hail mary. And in golf, it’s the 350-yard drive. The drive that makes 550-yard par fives reachable with 6-irons and renders long par fours defenseless against an onslaught of high-arcing short irons and wedges.

But the ball, many say, has simply gone too far this time.

Hootie and the Blowfish

Greg Norman spoke out against technology (while simultaneously switching to MacGregor’s new MacTec NVG driver and lauding their R&D). In fact, Norman explicitly called for a new set of rules for professionals, saying “put the restrictions on us. We are the best players. Don’t let us take advantage of technology like we have.”

The chorus of voices includes former PGA Tour Commissioner Dean Beman, who criticizes not only the distance but the lack of curve today’s ball exhibits. He wrote a letter to the USGA imploring them to legislate against technological advances in recent years in order to “protect and preserve the game of golf.” In his own words, “distance trumps everything.”

Golf course facilities are also taking notice, including king of them all, Augusta National. Augusta’s board is considering implementing a “tournament ball” during the Masters tournament. “The club wants to identify a threshold for distance that, when reached, would trigger a rollback in how far the balls goes,” a source close to the club is quoted as saying. “While the club would prefer that the USGA and the R&A take the lead, it would also not hesitate to act unilaterally to protect its course.”

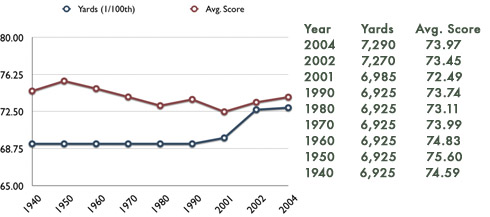

Augusta National has done a little over the years to mitigate the threat of distance, but the numbers are, to many, undeniable. Gene Sarazen holed a 4W on the 15th for double eagle en route to winning the Masters in 1935. The hole measured 485 yards in 1935, and today measures 500. Players routinely reach the green with 5- and 6-irons.

The Laws (and Rules) of Distance

Before we go hog wild in blaming the ball, the drivers, and the equipment, let’s take a look at some of the science – the laws of physics – as well as some other laws – those established by the USGA and called simply “The Rules of Golf.”

The buzz phrase – or, more accurately, acronym – these days is “CoR,” which stands for Coefficient of Restitution. We could give you the complex definition, but former USGA Technical Director Frank Thomas’ explains it well enough. The CoR measures the efficiency of energy transfer between two colliding bodies (i.e. a driver and a golf ball). He provides the example of a ball fired at a steel plate at 100 MPH, rebounding at 75 MPH. The CoR of such a ball at that speed is .75 (75/100). Given that clubheads are not solid steel plates, the following formula is useful:

The recent debate in driver technology has centered around the “spring-like” effect. Though spring-like effects are against the letter of the rules of golf, nearly every thin-walled titanium driver features a small spring-like (or “trampoline”) effect. Older, thick-walled, steel-faced drivers exhibit little or no spring-like effect and exhibit a CoR of about 0.78.

In 1998, the USGA set a limit on the CoR at 0.83 (0.822 plus a test tolerance of 0.008). The difference between 0.78 and 0.83 provides real-world distance returns of about 10-15 yards. Because golf balls themselves have varying CoRs, the USGA tests metal woods using a metal sphere similar in size to a golf ball.

Of course, not only metal woods are subject to rules: the performance of the modern golf ball is heavily legislated as well. The Overall Distance Standard, or ODS, was adopted by the USGA in March, 1976. The ODS limits the average distance of a brand and type of golf ball to 296.8 yards when hit with Iron Byron, the USGA’s “iron horse” testing machine, at a swing speed of 109 MPH. No ball which conforms to the weight, size, and initial velocity specifications has ever failed the ODS.

With better science comes better understanding, and this is true with golf balls as well. Iron Byron’s launch conditions are quite well-known and have been fairly rigid since its introduction in the 1960s. Today’s understanding has lead to the “high launch, low spin” mantra, and today’s balls and drivers have been tuned to most closely match these conditions while remaining within the ODS. The demand to better test balls fell once again to the USGA. Specifically, to determine a ball’s optimal launch conditions and to test distance under those conditions.

With better science comes better understanding, and this is true with golf balls as well. Iron Byron’s launch conditions are quite well-known and have been fairly rigid since its introduction in the 1960s. Today’s understanding has lead to the “high launch, low spin” mantra, and today’s balls and drivers have been tuned to most closely match these conditions while remaining within the ODS. The demand to better test balls fell once again to the USGA. Specifically, to determine a ball’s optimal launch conditions and to test distance under those conditions.

In response, the USGA invested millions of dollars in the development of the Indoor Test Range (ITR). The ITR is a glorified wind tunnel that allows the USGA to identify the aerodynamic fingerprint of a golf ball, so to speak, allowing the entire ball flight to be simulated. Sixteen different ball speeds and spin rates are used to determine the fingerprint and thus flight characteristics. Combined with information about the initial ball speed, the USGA can test balls year-round and achieve incredibly accurate numbers under the ball’s ideal launch conditions.

Of course, today’s pros don’t swing at 109 MPH. Because a golf ball can be built with different layers, faster swing speeds interact with increasingly deeper layers of the ball. Imagine a ball that had a small but very, very high-energy core. A 109-MPH swing speed may not compress the core and would fail to tap into its tremendous power. Put the ball at the end of Tiger Woods’ 130 MPH swing speed, though, and BAM!

After all, drivers are getting longer and players are in better shape. Graphite shafts and titanium heads have reduced driver weight. The 109 MPH swingspeed used to determine current distance standards is not entirely representative of today’s tour player. To counter this, the USGA and the R&A are considering amending the Overall Distance Standard to include a limit for a ball hit by a club swung at 120 MPH. The number being tossed around is 320 yards. The average PGA Tour player swings at between 116 and 120 miles per hour.

Frank Thomas says:

This new test method will result in an increase in distance for every ball. Some balls will go as much as 10 or more yards longer under the optimum conditions, compared to the old test method. (The optimum launch angle, by the way, is about 13 degrees, and the optimum spin rate is about is about 1,500 revolutions per minute. And guess what? These are not far off Tiger Woods’ actual, real-life launch conditions.)

Frank Thomas also says that recent distance gains have come as a result of “the combination of springlike effect and the ball. Once you’ve married those two, there’s no room left. We’re not going to see anything, anything at all, like we’ve seen in the last eight years.”

The legislation is there. The rules are there. Balls – and the drivers that hit them – can’t go much further. Between the CoR rules and the ODS, club- and ball-makers have hit a brick wall (or, in this case, a steel plate or metal sphere). All they can do now is fine-tune and, essentially, advertise and market their balls to differentiate them from the others. The difference between a Nike One Black, a Bridgestone B330, and a Titleist Pro V1x is less than 2% for any given player. The USGA has a cap on the technology.

Scoring: The End-Game

New Zealander Frank Nobilo says that “as long as he is a worthy champion and the course has been fair, I don’t think the score matters. [The] USGA [hates] having the winner of say the US Open in double figures under par. So they trick up the golf course, like they did at Shinnecock Hills last year. It was just about unplayable.”

Are we a nation of golfers obsessed with the score? If we are, then simply blaming distance for plumetting scores is hardly fair: it deserves a good, hard, honest look.

PGA Tour driving distance has increased from 255 yards in 1968 to 278.5 yards in 2001, a 23.5-yard increase in 33 years. Over half of that gain – 14.3 yards – have come in the past six years. Surely that has led to a drop in scoring, has it not?

PGA Tour driving distance has increased from 255 yards in 1968 to 278.5 yards in 2001, a 23.5-yard increase in 33 years. Over half of that gain – 14.3 yards – have come in the past six years. Surely that has led to a drop in scoring, has it not?

In the last twenty years, the number of putts per round has dropped 0.65 strokes per round and the scoring average dropped from 71.9 in 1968 to 70.88 in 2001, or 1.12 strokes in 33 years. Are players getting closer to the hole? Probably not: average green-in-regulation (GIR) percentages have only improved 1.5% in the past twenty years. Greens are quite a bit smoother these days than they were in 1981 (or 1968).

Frank Thomas says that “test data indicates that the ball most commonly used on the Tour for almost 50 years improved in distance by approximately 10 yards up until two years ago when the new multi-layered balls were introduced… These travel about 8 to 10 yards longer than the older wound construction design.” All told, we’ve seen an equipment improvement of 20 yards from fifty years ago. That’s a club and a half, folks.

The Real Technology Advantage

The USGA has limited the CoR. They’ve tested the ODS and are looking to amend it to handle today’s faster swing speeds. Balls and clubs simply can’t go further on their own. Why are players scoring so well, shattering championship records left and right, and leaving the hallowed courses of yesteryear in the dust?

Contrary to what Deane Beman believes, I don’t think distance is everything. Today’s player is scoring better for several reasons, and distance isn’t really one of them.

Forgiveness

First, today’s clubs are more forgiving. Jack Nicklaus, playing thirty years ago with a small-headed persimmon driver, could not really go after a ball. Modern drivers have “expanded sweet spots” that are larger than some of the older persimmon clubs! A pop-up or a heel job thirty years ago is 290 in the left edge of the fairway today. Put 460ccs in someone’s hands and they can let out a bit more shaft. A “miss” in the persimmon-wood days landed 50 yards out of bounds. Today you’re in the first cut of rough.

Spin

Grooves and the ball cover material have advanced so much that generating plenty of spin from the rough is no longer a challenge. Modern irons and balls rarely produce fliers. It’s not unusual to see a player stick a ball on a firm green from 150 yards out of the secondary rough. This has little to do with distance. thirty years ago, you had to hit the fairway to get close to pins. Today, players would rather hit a wedge from the rough than a 7-iron from the fairway because they’re able to generate spin and to get close.

Launch Monitors

Our ability to measure things – such as launch angle, spin rates, and ball speed – has had a huge impact. Modern players can now perfectly match their driver and their ball to achieve optimal distance for their swing. Top-ranked players have balls specifically created for them. Don’t think so? Tiger plays with a ball you can’t buy. So does Phil.

The Lob Wedge

Players today miss just about as many greens as they did in the past (again, a 1.5% improvement in 20 years). Frank Nobila points the finger for lower scoring at an unusual suspect, the shortest club in the bag that doesn’t roll the ball on purpose: the lob wedge. “I think the lob wedge is the worst thing. When you miss a green on the short side, you can still save par with a 60 or 64 degree wedge shot which will land softly. That’s the equipment allowing a player to go unpunished after a poor shot.”

Players today miss just about as many greens as they did in the past (again, a 1.5% improvement in 20 years). Frank Nobila points the finger for lower scoring at an unusual suspect, the shortest club in the bag that doesn’t roll the ball on purpose: the lob wedge. “I think the lob wedge is the worst thing. When you miss a green on the short side, you can still save par with a 60 or 64 degree wedge shot which will land softly. That’s the equipment allowing a player to go unpunished after a poor shot.”

One only has to think of Tom Kite. Kite, a short hitter in just about any era, was the first PGA Tour pro to put a third and a fourth wedge in his bag and immediately began winning tournaments, including the US Open in 1992. His weapon was not the driver, but the wedges. Justin Leonard, Phil Mickelson, and even Tiger Woods are masters of the wedge, and they’ve won four of seven tournaments on tour.

Straight Shots

For Nobilo, though, it’s more than the lob wedge. Nobilo also attacks the ball, but not for being too long. Nobilo thinks that the ball is too straight. “Today’s ball is designed to fly high and straight and stop quickly. A pin tucked tight can be attacked with a high, soft shot, even with a medium or long iron, because the ball will stop quickly. In years gone by you had to shape a shot to get the ball close to tight pins.” And hey, you miss the green, you lob it up and save par.

Course Conditions

Course conditions have improved dramatically over the past few decades. The days of getting a bad lie – even in the rough – have passed. Balls roll smoothly on greens and more putts drop. In a 2002 survey of Golf Course Superintendents Association of America members, over 38% of the members attributed improved distance to improved golf course conditions. Over 95% of those surveyed also say that golfers have increased expectations for course conditions.

Augusta National is leading the charge for a tournament ball in many people’s eyes, but who can think of a course with smoother greens, faster fairways, and less rough? The course has been lengthened 365 yards since 1940 – an average of 20 per hole – but the length has only made a small impact on scoring. From 1940 to 1980, players improved less than 1.5 strokes. In 1990, the average scoring increased despite the fact that the course played to the same length.

Player Conditionining

There’s little doubt that today’s player is in better shape than the player of yesteryear. Nicklaus was quickly nicknamed “Ohio Fats” when he sauntered onto the PGA Tour in 1962. Ligher clubs have contributed a little to the increased swing speed, but there’s no arguing with the successes of today’s golfer. Every successful PGA Tour player follows a strict workout regimen. Today’s PGA Tour players are athletes. You’d be hard pressed to say that of golfers in the 1960s.

Preserving the Old Courses

Nearly every debate involving the distance today’s pros hit the ball involves one opinion. It keeps popping up, but its presence is never justified. You’ve probably uttered the words yourself: “We must preserve our courses. Today’s technology is rendering the famous older courses obsolete.”

Tell that to the Old Course at St. Andrews. Tell that to Pebble Beach, Spyglass Hill, and Poppy Hill – three courses that measure “only” 6800 yards apiece but have withstood the test of time despite a winner – who did not break the all-time scoring record – who admits that he’s hitting the ball 15 yards longer and “chipping” drivers 290 yards.

As players improve – as the game changes – new courses will better test players. Some old courses can be lengthened, but expecting a course originally played with persimmon woods and wound balls to play stiff in the modern day is often asking too much. The course still provides an adequate test of golf for the slightly less skilled. Merion Golf Club, the famed club outside Philadelphia, has not hosted a PGA Tour event in years but will test the world’s best amateurs at this year’s US Amateur.

Tradition is important to golf, and perhaps tradition and tradition alone explains the need some people have for “preserving” old courses. The USGA “tricks up” courses to preserve par while the PGA simply finds new courses that better test today’s players.

Sorry Deane, But You’re Wrong

Despite what Deane thinks, distance is not everything. Today’s PGA Tour player is in better shape, plays in better conditions, and has a better understanding of the golf swing and the science behind it. He’s got a lob wedge, a “forgiving” driver, and a straighter ball in his bag. He’s ready to win.

Once again, Frank Thomas summarizes things nicely:

We have to use science to preserve the challenge of the game. We cannot have two sets of rules. It would destroy the relationship between the ordinary golfer and those at the top. If there is a ‘problem’ it is only with 1% of players and if those players retain the same strength and fitness as today then there is only potentially another 15 yards to go.

Distance isn’t everything.

Limiting the discussion to the distance the ball flies may cause more harm to the game than an extra 10 yards ever could.

Photo Credits: © TourCast, © TechImaging, © Louisville Golf, © Cleveland Golf.

Interesting, and well researched story. That said, I have a real issue with thinking Merion will test the best players at this years am.

You’re probably right — but at what cost? Merion has spent a lot of time and money trying to squeeze new tees in all over the course to gain even a few yards in the hope of protecting Hugh Wilson’s masterwork from being beaten up by some long-hitting college kids.

Tees, like on the sixth hole, are now pretty much in the firing range of the par five second. It is kind of ridiculous — the efforts some courses have had to go to protect par. Tiger proofing? How about ProV proofing.

The COR formula is confusing. First the comparison of hitting a golf ball with club to a golf ball traveling 100 mph and hitting a metal wall and bouncing off at 75 mph is made. First, a ball going 100 mph and bouncing off the wall would have to come to a complete stop as it hits the wall and then change directions. Compare this to a ball that’s stationary and then struck by a club at a rate of 100 mph. The ball would start its ascent at 100 mph and then its speed would decrease. To make this connection between the two examples would be incorrect since the conditions are different between the two examples.

George, in purely scientific (and practical) terms, you’re incorrect. The objects relate to each other. In both instances, the centers (of the club and the ball) first get closer to each other, then pause, then move away from each other.

It matters not in measuring CoR which is actually in motion first. The physics is the same regardless.