Throwing Darts returns with golf course architect Ian Andrew, owner of Ian Andrew Golf Course Design. Ian worked with Doug Carrick of Carrick Design for 17 years before leaving in 2006 to open his own firm.

Throwing Darts returns with golf course architect Ian Andrew, owner of Ian Andrew Golf Course Design. Ian worked with Doug Carrick of Carrick Design for 17 years before leaving in 2006 to open his own firm.

Ian is best known for his restoration and renovation work of golf courses in Canada. Ian started a blog called The Caddy Shack to detail his thoughts on golf course architecture as well as to give us an insight in the day-to-day operations of running his own design company. It has been interesting to read the daily posts on the current state of the game as well as the projects he has been working on. Ian also shows considerable passion for promoting the great history of golf course architecture which includes Stanley Thompson, Alister Mackenzie H.S. Colt and Charles Alison just to name a few.

We hope you enjoy this interview.

TST: You have recently decided to go out on your own and start your own design company. What has been the most challenging issue you have encountered thus far on your own and what advice would you give others who may be considering opening their own design company? What advice would you give someone who is interested in golf course architecture?

Ian: I was in the business for 17 years before going out on my own, so I didn’t run into the usual difficulty of needing to find work. I had enough renovation clients that chose to continue with me that it eliminated a lot of the early pressure of trying to make ends meet. As a designer, my main difficulty is trying to find new course work in an environment where (in Toronto) there is an oversupply of golf courses.

Ian: I was in the business for 17 years before going out on my own, so I didn’t run into the usual difficulty of needing to find work. I had enough renovation clients that chose to continue with me that it eliminated a lot of the early pressure of trying to make ends meet. As a designer, my main difficulty is trying to find new course work in an environment where (in Toronto) there is an oversupply of golf courses.

The biggest challenge for me was dealing with the business side of the company; it takes much more time than I had thought. From liability insurance to accounting to marketing you need to understand an awful lot more about how to run a business.

As for my advice for someone looking to start their own golf design business: go get experience working for someone else first so that you understand how to build a golf course and how to run a business. Clients have to know you’re capable of doing the job before they hire you. Around Toronto, many of the projects handled by first time designers with no experience were disasters and have lead to bankruptcy.

I would also advise that people have a plan for how they are going to market themselves – a web site is not enough and introduction letters are generally a waste of time. You need to figure out how to get your message and name out in the public. To go on your own, you must have enough money already in place so that you can purchase the things you need and still manage to pay your bills if you’re having trouble finding work. You need the flexibility to get through the tough times.

I guess the final thing I would suggest is make sure you have the personality to do it. You must be very self motivated; it’s more important than talent. You must keep pushing to grow the company and get everything done on time. You also have to be self confident enough to shrug off not getting a project or having a slow period.

TST: What projects are you currently working on?

Ian: I’m lucky to be as busy as I am right out of the gate. I have over 20 clients and I’m actively working with a dozen clubs on various renovation and restoration projects. From Thompson to Colt & Alison, to Willie Park Jr. it’s been a fun start. The ones that likely interest people the most are the restorations of Stanley Thompson courses.

I’m currently spending a lot of time working with Kawartha Golf & Country Club and The Cutten Club. Kawartha is one of the best preserved of all Thompson’s courses and this is the final year of a major restoration that takes the course completely back to original Thompson design. While the course is lesser known than Thompson’s finest work, St. George’s Golf and Country Club – a club that I restored a few years back – it has been a real treat. Kawartha remains one of the only completely intact Thompson courses left.

I’ll begin a similar process with The Cutten Club, a course Thompson co-owned at the time of his death, but Cutten has farther to go with many of the original features being removed in recent times. I have learned a lot about recreating Thompson’s architecture over the last ten years and I feel I can take the Cutten Club close to what it once was. I really enjoy the restoration work.

TST: What styles and architects have influenced the design work you do today? What have you taken from them an applied in your own work, and how well have some of the features of older courses migrated into the modern world of golf?

Ian: The Golden Age of Architecture is without a doubt the high water mark of golf architecture. The work of architects like Alister Mackenzie, H.S. Colt, Charles Alison, George Thomas, A.W. Tillinghast, C.B. MacDonald, Seth Raynor, and Stanley Thompson still remain the ultimate benchmark of greatness for golf architects. Even their quality of the writing has been a huge asset to understanding how great golf architecture is created. The courses that they have built have become the foundation of great golf course architecture.

They have influenced me with the boldness of their architecture and how many of their courses feature a few holes that border on controversy. They never played it safe; they were always innovative in their approach and never afraid to push the boundaries of either the player’s ability or their art. They all certainly had a knack for finding the best holes in the landscape, even if it meant ignoring one stunning hole to find a better overall golf course. They most often found their greatest holes, but also had the ability to create them when the land was offering little assistance.

They have influenced me with the boldness of their architecture and how many of their courses feature a few holes that border on controversy. They never played it safe; they were always innovative in their approach and never afraid to push the boundaries of either the player’s ability or their art. They all certainly had a knack for finding the best holes in the landscape, even if it meant ignoring one stunning hole to find a better overall golf course. They most often found their greatest holes, but also had the ability to create them when the land was offering little assistance.

Finally, they all spent an inordinate amount of time on the smallest of details which is the most overlooked factor in creating a great course. I think it is also important to point out that architects like George Crump and Hugh Wilson were just as influential on architecture even with only one course.

I think it also important to recognize when peers have done some exceptional work too. If we ignore our peers, we limit what we can learn. I’m really enjoying the recent work of many of the so-called minimalists. Tom Doak and Bill Coore in particular, are creating exceptional courses and working in their own unique styles, which I enjoy. I find their architecture is firmly routed in the principles of the architects from the Golden Age. I’ve had lots of opportunity to talk with both and I find that our principles are very similar which give me a lot of confidence going forward to build my own courses.

My philosophy is I’ll borrow from any architect at any time. Every site has an example we can draw from to find the best solution. I believe, like C.B. MacDonald, that there are likely no new ideas and that is our responsibility to identify the best of what has been done and find new and interesting ways to apply them.

My first project makes a good example; it had no elevation change on the entire site, so I borrowed the concepts from Pinehurst #2. I raised the green sites up onto plateaus to add interest and challenge to the course. I created some very dramatic contoured greens to make the second shot and putting very difficult. I also borrowed Ross’s technique of using the drainage swales to create the appearance of elevation change.

People seem to enjoy the enormous amount of creative shots around the greens and don’t seem to notice that the site is still relatively flat. I believe you look to the best example you know that work and then try to improve upon this with you own ideas to add even more interest and fun.

TST: How would you describe your style of design, your “signature” if you will?

Ian: I think the architect’s responsibility is to make the game interesting rather than just aspiring to make the game difficult. A player should face a round full of options where they can take multiple routes or even hit different shots into greens depending on wind or their own ability. I believe in little earth moving, designing shorter courses, multiple short fours, very contoured and complicated greens, fairway width, opportunity for chipping, and building dramatic hand sculpted bunkers.

Ian: I think the architect’s responsibility is to make the game interesting rather than just aspiring to make the game difficult. A player should face a round full of options where they can take multiple routes or even hit different shots into greens depending on wind or their own ability. I believe in little earth moving, designing shorter courses, multiple short fours, very contoured and complicated greens, fairway width, opportunity for chipping, and building dramatic hand sculpted bunkers.

I don’t think I will ever have a “signature” or distinctive style because I want every course to be a response to the surroundings. From my point of view, anything else is an imposition on the land, and that doesn’t lead to great architecture.

TST: What are some of you favorite courses and what do you like/dislike about each?

Ian: My favorite five courses not named St. Andrew’s are the National Golf Links of America, Royal County Down, Royal Dornoch, Merion, and Pine Valley.

The National is the most entertaining course I have ever played. The course offers more variety than any other course, whether through a change in the wind or through different pin positions all the holes can change entirely. Each pin and wind requires you play either a different route or approach type; there isn’t a more fun course to play in golf. The beauty of the course is that it will remain just as fun and interesting when you are 70.

Royal County Down is shunned for all the blind shots but I wouldn’t change a thing. Each time you walk over the dune – that you just hit over blindly – your breath is taken away by the stunning setting of the rest of the hole. The course completely defies convention, yet everything about it makes sense. The front nine is with out a doubt the best single nine holes of golf in the world. It’s a shame the finishing two holes just can’t live up to the start because of the land on which they’re routed.

Royal Dornoch features some of the finest green complexes in golf. They range from the prominent plateaus that inspired Donald Ross so much that he brought them to America through to the greens that seem flawless extensions of their natural settings. The genius of “Foxy,” as well a many other green sites, teaches us that short grass can be just as good a defense as bunkers. Royal Dornoch is a wonderful place to rediscover everything that is right about the game.

The second green at Royal Dornoch showcases the green complexes Andrew calls “some of the finest in golf.”

Merion is the finest routing I have ever seen, it gets more out of a small property than any other course I know. I love the three-part act that makes up the course. Much of the length is found on a series of very strong opening holes. The player is enticed into getting aggressive through the wonderful collection of short holes that make up the middle. Finally he walks by the clubhouse to face the toughest finish that I have ever played. It is a wonderful study in rhythm, something very overlooked in routing. My complaint about Merion is the golf course is too narrow and the rough too long to be enjoyable or near as interesting as it really is.

Pine Valley remains the single best course I have stepped foot on. The variety of lengths and challenges is beyond any other course that I know. There is not a single weak hole or a weak moment on the round. The course pushes you and intimidates you till it inevitably will finally overcome you. On the other side, once you have played a few times, you discover there is plenty of room and the course is very fair until you make mistakes. I think the course is very overcrowded by trees and needs to be opened up a little; it certainly won’t be any easier since most of these areas are actually exposed sand or bunkers anyway.

TST: With much of your time spent on prospective courses or renovation work and research, do you get much time to actually play golf and if so do you enjoy your round for the pure sport of golf or do you spend more time looking at the architectural aspects of the course?

Ian: I did not play in July this year and this is quite common. I play an average of 30 rounds a year and a majority is in the spring or fall when I’m less busy. I always try to play when I get any opportunity to see a great course, but otherwise work usually takes priority. I don’t play at all on weekends because I consider that family time. I play to experience and learn architecture or to enjoy the company of friends.

TST: Did the explosion of golf courses in the mid 1990s harm golf as a whole with cookie-cutter designs created to cash in on a booming trend, or was the growth good for the game of golf?

Ian: Even bad architecture can’t really harm golf, but it certainly does make for a very weak business for the person who paid to build the course. That said I do think that some of the most important architectural work in the last 50 years has occurred at courses like Sand Hills, Pacific Dunes and Rustic Canyon. Golf architecture has once again made important strides in the right direction for golf. I do think the nineties will be another period where the most popular designers will have a legacy of quantity and not quality.

Where the build out of the nineties has hurt the game most is the cost of golf went up exponentially with each vanity-driven dream trying to outspend the last one. There is a remarkable willingness to buy into the concept that that a golf course is only great if it’s expensive. The result is participation in the game dropped because it is affected by economics – golf became too expensive for the average person. Again we will repeat the previous cycles, as prices drop with oversupply, the game will find its footing once again. As for architects, the oversupply means it will be harder for us to find new projects for the foreseeable future.

TST: Are modern golf courses too difficult for the average golfer as opposed to the classic designs that featured different levels of risk/reward based on a golfer’s playing ability? If so what features should be “re-introduced” to modern golf course design to make the game of golf more enjoyable?

Ian: Ninety percent of everything wrong with golf can be summed up by length. From the ball, to the additional cost of building new courses, the monotony of excessively long layouts, through to the loss of the short par four. Everything seems to be designed to host a PGA tournament – from the necessary length, perfect playing conditions, clearly indicated strategies, through to the gentle contours required for lightening-fast greens.

It’s like every architect and owner somehow feels their new masterpiece is destined to hold a tour event and they design their courses accordingly. These courses are generally way too difficult, feature little or no options and have a high green fee. If architects would return to building courses for those who actually use them we would have much better courses.

So what should be re-introduced? Golf courses need to be shorter and wider. Width introduces options for a better player and playability for the vast majority of players. Options lead to interesting choices, which lead to a more enjoyable golf experience. If we enjoy the game, we will play more. If participation rises, the health of the game improves, it helps all of us who love this game.

The 315-yard tenth hole at Riviera Country Club has been vexing the best for nearly a century.

Before anyone suggests short and wide courses are too easy, just look at the scoring average for the tenth hole at Riviera during the Nissan Open. Difficulty and length are not a direct correlation. Just think of Merion and Pine Valley, two courses that are very difficult despite being short by modern standards.

TST: A lot of former and current PGA Tour professionals design golf courses but the rare exception actually go and visit the site and take a hands-on approach as opposed to just lending their name. Do PGA Tour professionals make good golf course architects? Does being a good golfer give you an advantage as an architect that a poor golfer doesn’t get?

Ian: PGA professionals can make good golf architects if they care enough to learn about golf architecture, but very few make the commitment to learn the profession. Often, course design is seen as a way of extending the “earning years.” Golf architecture involves a massive commitment to understanding the art and science of the profession and I don’t believe that you can dedicate yourself to continuing to play and practice golf architecture at the same time. There’s not enough time to be good at both.

Hitting the golf ball well has never been a prerequisite for becoming a golf architect and sometimes can be a detriment to comprehending how the majority of golfers play the game. Sometimes being too strong a player can be a detriment to understanding the limitations of the average player and just building shorter tees is not enough. I think it’s important to note that none of the recent ten best courses have come from golf architects who played professional golf.

Yet former professionals tend to demand fees that range from double to ten times more than the average rate for golf architect. Their construction budgets and maintenance budgets tend to be usually double the cost of a course built by people who never played professionally. Still, non-professionals have consistently turned out far better courses. This begs to question about the real value of a name beyond initially attracting players when a less expensive course will generate a quicker and more consistent return.

TST: What advances in agronomy have helped or hindered the maintenance of golf courses?

Ian: I’m in awe of what superintendents can do on a day-to-day basis, but I also think some of their enormous skill has been detrimental to the game. No other change in agronomy has been more responsible for removing creative features from design than increased green speed. Modern greens are flatter and less engaging to play than the greens with complicated contours.

The increasing speed of greens is also a huge detriment to the preservation of great architecture because courses are feeling pressured to renovate their original architecture due to increased speed. I will say the shorter turf around the greens has been an enormous improvement to the playability and options found in chipping areas. This has been a huge boost to the quality of the game.

TST: More modern courses are moving towards or are already “motorized carts only.” What do you think of golf carts and the role they play in golf course architecture?

Ian: I believe that motorized golf carts should only be allowed for players with a doctor’s note and an inability to walk nine or eighteen holes. The courses in Scotland and Ireland are much more enjoyable experiences because they don’t have cart paths. The argument in favor of golf carts is that they allow us to use sites that are severe, but I think that has become a detriment to producing a good routing, too.

Ian: I believe that motorized golf carts should only be allowed for players with a doctor’s note and an inability to walk nine or eighteen holes. The courses in Scotland and Ireland are much more enjoyable experiences because they don’t have cart paths. The argument in favor of golf carts is that they allow us to use sites that are severe, but I think that has become a detriment to producing a good routing, too.

Many courses drive all over Hell’s Half Acre to find only the “best holes” and this leaves us with a disjointed course that feels like a road trip rather than a “walk in the park.” The routings for cart courses tend to have you drive up to the highest point and play downhill, how much variety to the routing is lost by this tendency? Not every great hole goes downhill through a natural valley.

The other issue I have is the assumed dependence on cart revenue to make ends meet. Look at the up-front cost of asphalt or concrete paths, the cart storage facility required, and the carrying cost to borrow that amount. Now add in the staff to manage them, the repairs to the course associated with cart use and cost to keep changing over the fleet and I ask you how carts can be considered a big revenue generator.

TST: Despite the advances in golf technology, the average golfer’s handicap has not changed much. Has too much been made of technology advances?

Ian: No, not enough has been done about technology. The changes in technology have made the best players even better and have done little to help the average player. Golf architects are left unsure how far the technological advances can possibly go, which leaves it very difficult to place carry bunkers and develop risk and reward scenarios. Each time we think we are developing a situation to test the bravado of the better player; they seem to gain a technological boost that renders our strategies obsolete. Just planning or adding “another” back tee just doesn’t cut it anymore. You can’t design a course that plays the same from tees ranging from 5,000 yards to 7,500 yards. We also can’t afford to lengthen and widen courses forever because the land costs alone would eventually strangle the growth of the game.

I also fear that some of the greatest architecture in the game may disappear for the same reasons. The amount of lengthening going on at classic courses for major championships has been staggering. We are changing strategies and shot values on some of our most treasured courses all in the name of professional golf and keeping up with technology.

It’s time to separate competitive golf from casual golf. I like to use baseball to illustrate how simple this would be to fix. Professional baseball players use wooden bats, college players use aluminum. Same game, same skills, but ball flight is cut down to reward skill. This hasn’t ruined baseball or the development of the next generation of baseball players. The tournament golf ball is such an easy answer to all the problems of length. The other alternative is to slightly enlarge the ball which would also reduce the flight distances and make the ball easier to hit for the average player.

TST: Do you feel the USGA is looking out for the best interest of the game or “bowing” to club and ball manufacturers with their lack of ruling for the latest driver and ball technology and if so, what can (and should) they be doing?

Ian: Their job is to protect the best interests of the game and to promote growth in the game. By not dealing with the ball, they have failed to protect the game, in my opinion. They have the financial ability to take a stand, yet they seem to be more worried about the money that it may cost them to do so rather than what it will cost the game down the road.

Ian: Their job is to protect the best interests of the game and to promote growth in the game. By not dealing with the ball, they have failed to protect the game, in my opinion. They have the financial ability to take a stand, yet they seem to be more worried about the money that it may cost them to do so rather than what it will cost the game down the road.

The funny part is the people who make the ball have already prepared for a reduction in the distance of the ball and have even prepared new balls to deal with regulation. I think the USGA needs to step up and regulate. If the threatened lawsuits occur, I think the golf community just might actively boycott their product on principle.

TST: What are your thoughts on courses being allowed to limit golf equipment technology on their own (i.e. use of a Masters specific ball, etc.) in order to keep them “competitive”?

Ian: I’m all for it, and I always hoped the Masters would lead the charge, but I now doubt that will happen. The story I heard was that The Masters was set to use a Masters ball but was convinced not to go forward with it. That being said, the use of a tournament ball in Ohio was a big step and opens up the chance of other States and regions taking a similar stand. It’s like The Memorial’s choice of bunker preparation to make a hazard a hazard. I commend any of those groups for taking a stand and offer my support to each. Bringing the equipment and conditioning back a step will place a larger premium on skill over length.

TST: Speaking of the Masters, what are your feelings towards the “renovations” that have been conducted at Augusta National within the last few years?

Ian: Bobby Jones and Alister Mackenzie built a course based upon the playing characteristics of The Old Course at St. Andrews. Augusta was a course full of optional routes with many alternative types of approaches available into most greens. The “new” Augusta National is not the course they set out to create. In fact, it has become the antithesis of everything Jones and MacKenzie set out to do.

Andrew: “The ‘new’ Augusta National is not the course [Jones and MacKenzie] set out to create.”

Where the course once featured width to allow for positional play to access those wonderfully intricate pin positions, it has now been turned into a single-option test of execution through the tree planting and rough. It still has many of the exceptional holes that make it great, but Augusta has simply had one too many bad facelifts to remain the beautiful design it once was. I think it all went wrong once they set out to defend par at all costs. The philosophy of Jones and Mackenzie was pushed aside for a new vision of the game. Now we have another tournament like the U.S. Open, where the player making the least mistakes becomes champion. I long for the Masters where the player willing to take risks usually wins.

Just about every course that hosts a major is being modified – usually to find length. The legacy of courses that have been irreparably damaged by alterations for a major is long, yet we continue to risk permanently damaging even more. We need to stop altering them to deal with technology. All we are doing is masking the impact of newer technologies by extending the courses. If we left our classic courses with their original architecture, players would go low and the industry would have to respond to the technological advances.

The PGA Tour is run by the players and for the players. If we left golf renovations up to the whims of the PGA Tour golf architecture, everything will be well-defined and completely fair. That is not the description of any of the greatest holes or courses this game has to offer. Just look at all their TPC courses (except the earliest ones). As the players got more involved with the design, the architecture has become increasingly sterile and safe. Once again I point out; the greatest holes push the envelope and often elicited criticism.

TST: You mentioned a concern about people not being able to afford to play golf due to the technological advances in golf equipment leading to longer courses (higher land cost, etc) yet there seems to be an overabundance (and in some cases over saturation) of courses in some parts of the United States. Why do you think this is? What do you see the future of golf course architecture, the continued building of high dollar courses that few can play or the building of affordable courses “for the masses?”

Ian: In all industries, people see others making money and try to copy the same model not realizing that one success does not guarantee the next one. Golf is no exception to this copycat mentality. There will always be the vanity driven big budget courses that are really not about a good business model – most of those have more to do with leaving a personal legacy. The problem is when there are only high-end projects being built, golf becomes too expensive and participation eventually declines.

A friend of mine says that most of these projects are built for the next owner, who buys it out of bankruptcy to make money. There will always be room for smart affordable business models like Wild Horse or Rustic Canyon. In the future, I believe that golf courses will have to be built with lower costs because that is the only business model that has proven to be successful.

TST: What are your feelings on the current state of the game of golf, and more specifically, golf course architecture? What do you think the next 10 years will hold? 25 years?

Ian: I think the next generation has demonstrated that they care about what is going on in the world around them and aren’t afraid to speak up for what they believe in. And I’m not just talking about golf, although this level of conviction does carry over into the golf industry. They care about the environment, the preservation of our culture and history, value quality over quantity and have embraced craftsmanship over mass production.

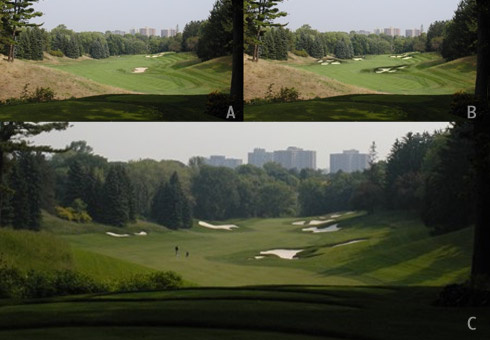

Ian has worked with St. George’s Golf & Country Club to renovate the classic Stanley Thomson design. Here, the 11th hole showing (A) its current state, (B) the proposed renovations, and (C) the final product.

In golf you’re seeing a return to a more traditional set of values. There is a lot of preservation and restoration of important golf courses going on. Courses are far more sensitive to the surrounding environment and many even rehabilitate lost landscapes. More care is being taken to build more responsible courses. I think future architects will build far fewer courses and build them with more detail and attention. I’m very optimistic about the next generation of golf architecture. We may not match the quantity of great courses designed during the Golden Age, but I think we will achieve some of the same high quality.

TST: Thank you for answering our questions. Interested readers can find Ian’s blog at http://thecaddyshack.blogspot.com/ and his design company at http://andrewgolf.com/.

Photo Credits: © Andrew Golf, © Beacons Field Golf Club, © Royal Dornoch, © Golf Club Atlas, © Anco Golf Cars, © Everett, © Andrew Golf.

Good interview, I liked what he had to say. I hope to play Sand Hills Club which he mentions a couple of times, someday?

Excellent article and questions.

I enjoyed reading Ian’s comments about course design and the golf course industry.

Ian has a unique perspective, which usually brings some great thoughts and ideas. I had not thought of enlarging the golf ball as an option to slow down distance gains, but it certainly would achieve that and help the average golfer make better contact.

Interesting concepts.

I enjoyed the interview… immensely. Although completely unfamiliar with his work, I share most of his sentiments when it comes to course design today. I’ve played too many courses (including Nicklaus’) that require no creativity or give options for alternate strategies. Hopefully, one day, I can play one of his designs and judge for myself.

Well done… both of you.